A typical weekday afternoon at The Armory in Manhattan’s Washington Heights neighborhood exemplifies New York City in microcosm as hundreds of high school athletes orchestrate organized chaos while practicing on the building’s legendary indoor track. Despite regularly witnessing this phenomenon, its splendor is not lost on Armory co-president Jonathan Schindel. “To me,” he observed, “it is a beautiful mosaic of New York City and the sport intertwined.”

The Armory is among the speediest and most renowned indoor track facilities in the United States. That its six-lane, banked 200-meter Mondo track is frequently cited as one of the world’s fastest speaks in part to the colossal, state-of-the-art overhaul that transformed the facility in the early 1990s, and in part to the caliber of local, regional, national, and global athletes that combine to log over one million miles on its hallowed lanes each year.

“Whether the last time you ran was on your high school track and field team or you’re an Olympic gold medalist,” Schindel remarked, “we want each of those two categories of people to look back at their experience at The Armory saying, ‘Boy that was cool, I’m never going to forget that.’”

What has been largely forgotten, overridden by these awe-inspiring contemporary Armory experiences, is that long before the Mondo track or its current Nike sponsorship, The Armory had previously endured two distinctly discrete, increasingly dismal existences. Built in 1909, it opened in 1911 as a military hub with a primitive track that improbably fostered the city’s indoor athletics scene, then in the 1980s became a men’s homeless shelter that, even more improbably, continued hosting track practices while its residents watched from the infield.

Perhaps most improbably of all, The Armory now thrives as a bustling track and community-oriented facility. The Armory has always been a mosaic of sorts – just not one that, until relatively recently, could be described as beautiful.

According to the New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs, from the late-1700s until today, New York City has had a total of 47 armories, 20 of which have been in Manhattan. These colossal structures were purpose-built to house local regiments of the state’s volunteer militia, typically with a massive drill floor designed for military exercises and storing heavy equipment. Of the two dozen or so armories scattered throughout New York City today, some are vacant, others are homeless shelters and a few are completely reimagined spaces that belie their militaristic roots.

One of these revitalized armories, referred to in state records as the Fort Washington Avenue Armory, is now known simply – and commandingly – as The Armory. Located at West 168th Street and Fort Washington Avenue in Washington Heights, it was built to house New York’s 22nd Regiment with 96,000 square feet of open space vast enough to hold military training drills and sturdy enough to store tanks – all on the building’s third floor. The Armory established a side hustle of hosting track events from its earliest days, and its first meet, the Xavier Games, was held in January 1914.

According to Jack Pfeifer, former director of college track and field at The Armory and unofficial Armory historian, The Armory was one of at least ten in New York City that hosted track meets in the 1920s, so it wasn’t particularly unique from the outset. Over the years, however, its accessible Manhattan location and relatively cavernous spectator capacity of 5,000 seats, plus bleachers that could be unrolled to add 2,000 more, made it a more desirable venue than other armories.

The track itself, however, was far from desirable. “It wasn’t really a track, it was just a wooden floorspace that they figured out they could use for running,” Pfeifer explained. “It wasn’t anything that had lanes marked on it. Eventually they marked lanes on the straightaway, but not on the turn. They just put little barricades out to create a 220-yard space.”

A banked track debuted at The Armory in 1922 for the inaugural Intercollegiate Association of Amateur Athletics of America (IC4A) indoor championship meet, presumably to signify speed and initiate interest in the nascent competition. Over the years, the banked track was rarely used outside of IC4A events, yet its very existence bolstered The Armory’s reputation as an indoor track destination. Most notably, The Armory became a hotbed for high school meets and practices – a legacy that remains to this day.

The Armory’s long and storied history of athletic excellence is observable in the form of small plaques that currently line the building’s main staircase from the ground floor up to fourth floor. Each plaque, ordered chronologically, details a track and field record – whether at the high school, collegiate, American, or world level – that was set in the building. Pfeifer conceived of this extensive display, then spent years determining what the various records were at various points in time so he could establish which had been set at The Armory.

The very first plaque represents the high school boys’ national 880-yard record, set at the Dewitt Clinton Games on March 28, 1914. At first, recalled Pfeifer, some people thought the procession of plaques would be “ugly and stupid,” but the self-identified history and stats guy proceeded undeterred until he had captured four floors’ worth of The Armory’s record-setting performances.

“I was concerned that it was a famous building, and that its history hadn’t been documented – and that the history would be lost if it wasn’t done,” Pfeifer reflected.

“It’s got the history that makes it the wonderful, breathtaking arena that it is today,” noted Marc Bloom, a lifelong runner and track and field writer who first ran at The Armory in December 1962 and has consistently returned as a journalist, spectator, or masters competitor.

As a teenager, Bloom was intimidated when he first started competing at The Armory, and not just because of his imposing opponents from all five boroughs and myriad backgrounds. It was also the two-hour public transit commute from Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn to West 168th and Broadway, then entering the building and navigating the active – if subdued – military presence, noticing the glass cases of military memorabilia, and passing by an actual tank in the hallway. All of this, Bloom recalled, to run on that same old track that wasn’t really a track. “It was a makeshift operation with wooden flooring – planks of wood – that had been used by the military for decades, so to make a track out of it for competition a line was simply painted around it.”

As such, The Armory was formative for Bloom as both a person and a runner. “I was open to new ideas and welcomed this new culture to be impressed with and really be a part of. It helped define my worldview as I emerged from competing there in high school.” For better or worse, Bloom’s own 1960s and 1970s Armory heyday coincided with the beginning of the demise of New York City – and The Armory itself.

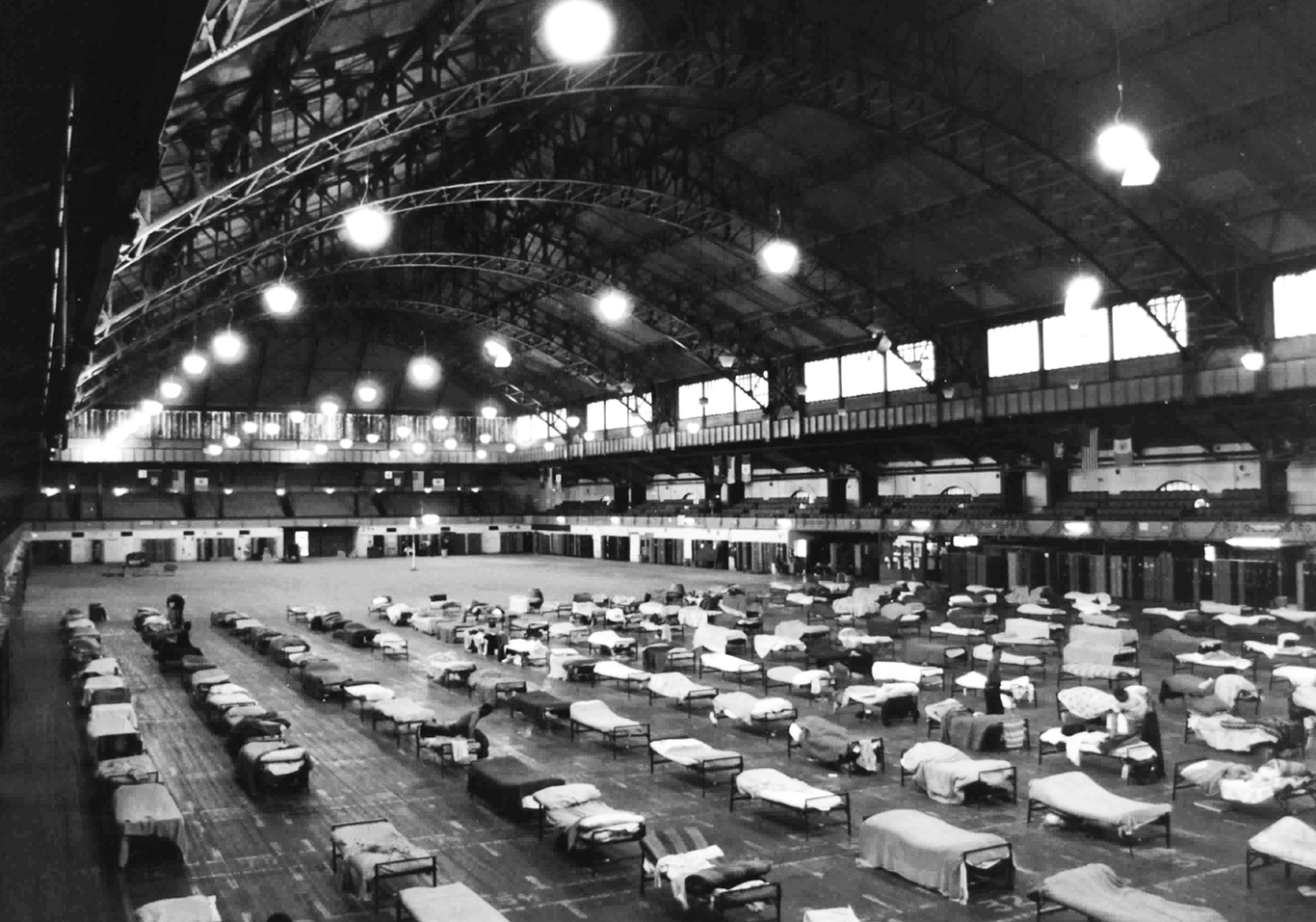

After narrowly avoiding bankruptcy in October 1975, New York City spiraled into a doom loop of economic and political struggles that manifested, in part, as a sharp increase in homelessness, crime, and drug use. After the city received a December 1981 court order to rapidly and immensely expand its shelter system, armories – many of which were either vacant or otherwise serving little purpose – became de facto shelters. The Armory, despite its small military presence and booming indoor track scene, was no exception. By the late 1980s, as many as 1,200 homeless men sought refuge on what was previously the track’s infield. The vast, open space that so perfectly suited the needs of militiamen and runners was also exceptionally well-suited to arranging rows upon rows of beds for New York City’s ceaselessly increasing homeless population.

The Armory quickly devolved into a dingy shelter fraught with rampant drug use, senseless violence, and squalid living conditions. A February 18, 1988 New York Times article noted that instead of subjecting themselves to The Armory’s abject horrors, “many homeless men, fearing for their lives, prefer to sleep in the streets and the rail, bus and subway stations.”

And yet, local high schools were so desperate for indoor track space that some continued practicing at The Armory. The high school track and field championship meets and daily practice sessions that had for years defined both The Armory itself and the culture of indoor track in New York City writ large gradually diminished as the shelter steadily grew; however, a few intrepid teams would arrange for the beds to be consolidated in the middle of the space so they could run laps as the residents looked on.

“At first they tried to coexist, and you can imagine what type of coexistence that was,” Bloom observed.

“Finally,” Pfeifer reckoned, “the people who ran The Armory at that time threw in the towel and said ‘Ok, we’re out of here, it’s all yours.’”

And so, for about a decade, The Armory was commandeered for – and, according to some accounts, by – multitudes of homeless men. Then, in 1992, advocates for the homeless threatened New York City with a lawsuit pertaining to its shoddy shelter system, and the city responded by reducing and rehousing its sheltered populations. Within a year, The Armory was down to 200 residents and up to the top of the local news cycle as a political pawn for Mayor David N. Dinkins, who, in an election year, campaigned in part on grand visions of embellishing the existing Armory structure with an apartment tower for poor and middle-class residents, a daycare center and a community theater – in addition to refurbishing the track.

Of those grand plans, only the track renovation came to be – and only because that idea was in motion long before Dinkins had ever even considered a reelection bid.

Dr. Norbert Sander, an internist who specialized in sports medicine and won the 1974 New York City Marathon, had the vision and clout to restore The Armory as a world-class indoor track. A lifelong New Yorker, Dr. Sander had run at The Armory in his youth, and in 1991 earnestly told the Times that “Running track changed my life.” He believed that The Armory’s closure as a track venue in deference to the homeless was unfair and damaging to high school kids in New York City who, throughout the 1980s, had been stripped of a venue to safely train or run their indoor meets. As a most grandiose gesture fueled by his deep love for track and field and even deeper nostalgia for his own seminal years of running at The Armory, he vowed to reclaim and revitalize the building.

“He was a sheer force of nature, Dr. Sander,” recalled Armory co-president Rita Finkel.

“He was such a good guy. Just a sweetheart,” Bloom gushed.

“He was a little nuts,” Pfeifer professed, not unkindly. “But he was also the kind of guy who, once he made up his mind, thought, ‘Oh, why can’t we do this?’ So once the city said no, well, that just made him all the more determined.”

Both Finkel and Pfeifer independently recollected that Dr. Sander cunningly cajoled the city into giving him the keys to The Armory.

“He made a deal with the mayor, saying, ‘Ok just give me the keys, I’ll take it from there,’” Finkel said.

“He was a very shrewd negotiator, to get ahold of those keys,” mused Pfeifer. “He knew, ‘Once I can get in there, they’re going to have a hard time getting me out.’”

With that set of keys, the city’s benevolent blessing, and $500,000 in donations solicited from corporations and private donors over a three-year period, Dr. Sander began the monumental task of eradicating the remains of the sordid shelter. Years later, he told Pfeifer that it took a full year after the shelter closed to air out the building and eradicate the ghastly smells that had permeated every inch of the space. To wit, in December 1993, Dr. Sander told the Times that “The smell of the place, the smell of the place could kill you.”

Once Dr. Sander got going, the renovation – which for any number of bureaucratic, logistical, and political reasons should have been a marathon-type effort – progressed at the pace of a 60-meter sprint. On July 29, 1991, the Times published an article titled “168th Street Armory; Reclaiming Track Is Runners’ Goal.” (“We’re trying to get back in there,” Dr. Sander said at the time.) Then, just over two years later, on October 29, 1993, the Times proclaimed “Armory Track Opens Again.”

The Armory reemerged as an ultramodern indoor track and field facility. Dr. Sander boasted that its brand new flat six-lane 200-meter Mondo track was just like the one used at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. A banked track – which Dr. Sander unabashedly touted as the world’s fastest – debuted in 1999. Track was back at The Armory.

In December 1993, the Times described the facility as an “astonishingly clean, well-lighted, fresh-smelling, state-of-the-art track,” and, in January 1998, marveled at its “new roof, new lighting, new speaker system and, this year, a newly painted ceiling. Light actually pours in from the outside.” To someone unfamiliar with The Armory’s history, cleanliness and light would hardly seem worth noting. But to those in the know, those attributes were nothing short of miracles.

Today, with Nike sponsorship in tow, the Track & Field Center at The Armory is perhaps best known as host of the esteemed Millrose Games, a premier indoor track and field event that attracts top talent from youth to masters athletes. In addition to Millrose, The Armory hosts over 100 track meets annually, with more than 180,000 athletes testing their mettle within the facility’s hospitable, if still intimidating, confines each year. The building also houses the National Track & Field Hall of Fame, as well as college preparatory and community-oriented programming for local youth.

Finkel, The Armory’s co-president, recalled that after renovating the building, Dr. Sander would watch the high school runners and, later, after they had graduated, ask their coaches what they were up to. She remembered him being dismayed if those kids, in whom he saw so much promise, hadn’t translated their learnings from running at The Armory to their post-high school lives. Finkel, whose sweet spot is “where underserved students, athletes, and education intersect,” channeled Dr. Sander’s dissatisfaction into various youth programs including Armory College Prep, which, in her words, helps with “getting seniors in high school into competitive four-year colleges with enough funding to make a college degree a reality.”

For the last eight years, every Armory College Prep senior – many of whom are first-generation college students – has been accepted into a four-year school.

The Armory Foundation also offers programs that currently support local community members from second grade through age 93. “We want everybody who comes in here to feel that we think they are tremendously important, and we are very focused on providing exceptional experiences,” Finkel asserted.

The Armory is a place where some people hope to blend in, while others aspire to stand out; where some realize their goal of pursuing a national record, while others realize their goal of pursuing a college education.

“Look at all the things The Armory offers to the thousands and thousands – over the years, hundreds of thousands – of kids,” Pfeifer said. “That’s the real mission, and that part has been a huge success.”

A beautiful mosaic, indeed.