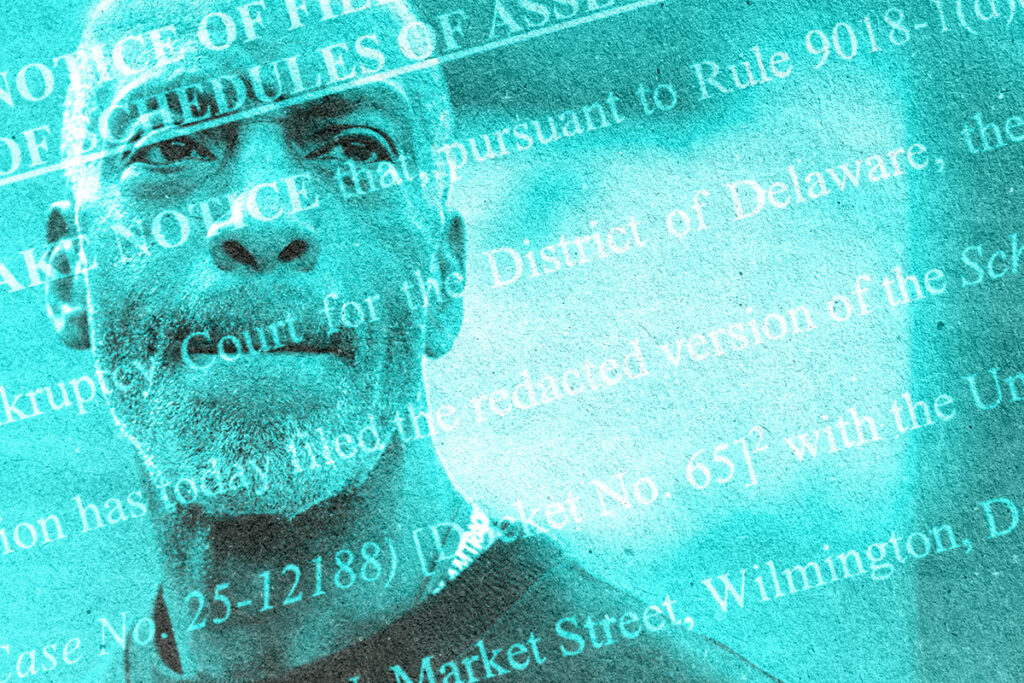

A clearer picture of Grand Slam Track’s finances became more apparent in its latest bankruptcy filing as new disclosures show that the league now owes its creditors over $40 million.

In a 221-page of assets and liabilities filed last Thursday in United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware, all of the creditors are named along with what they are owed and according to the document, less than $2 million in revenue was generated in the league’s three events last year.

The filing also shows that Grand Slam Track’s debts are around $10 million more than previously declared in the league’s initial bankruptcy petition.

This latest revelation is also the most extensive look at where the league stands as it has $831,385 in property assets which includes $143,286 in cash with a mix of 340 secured creditors, priority unsecured creditors and other unsecured creditors all detailed in the listing.

Of those classifications of creditors, $5,020,000 is owed to secured creditors, $68,295 is owed to priority unsecured creditors and $35,591,214 owed to all other unsecured creditors.

The bulk of the unsecured creditors includes athletes and vendors, with well over 100 athletes who were either contracted for all of the league’s four scheduled meets or competitors who were chosen to participate in at least one event.

Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone ($268,750), Kenny Bednarek ($195,000), Gabby Thomas ($185,625) Melissa Jefferson-Wooden ($174,375) and Marileidy Paulino ($173,125) lead the top five group of athletes listed with at least 70 others owed between $20,000 and $168,000.

But the biggest creditor is investor Winners Alliance, which has a claim for $5.02 million in secured creditor debt, in addition to $6.113 million for additional unsecured debt and $6 million as part of a SAFE investment that was initially funneled to Grand Slam Track as it began operations in April 2024.

Winners Alliance makes up around $17 million of debts, a significant portion of the $40 million owed despite being a single creditor.

Television production vendor Momentum-CHP Partnership is the second largest creditor at $3,035,584.

Meanwhile, Johnson appeared to have made a personal stake in trying to keep the league afloat and loaned the venture around $2.7 million of his own money in late May 2025. Grand Slam paid Johnson back $500,000 of the loan, but he is also listed as a creditor and is owed around $2.2 million.

Johnson, as league commissioner and an employee, was paid twice in December 2024, and drew paychecks from January 2025 to March of that year but was not paid again until August. His last payment as an employee was in November, just before the bankruptcy filing.

When the league filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in December, the full list of all of its debts were not finalized. And in last week’s disclosure, additional creditors were revealed including Rekortan, which resurfaces tracks along with several athletes like Nikki Hiltz and Cole Hocker, on air talent and a venue at UCLA where the final meet was schedule for June 2025 in Los Angeles.

Grand Slam Track’s complete strategy for its Chapter 11 plan must be issued by Friday and detail how the league can begin to pay its creditors.

At a meeting of its creditors on January 14 facilitated by the United States Department of Justice, a representative from Force 10 Partners, a corporate restructuring company for the league, said Winners Alliance has provided a $3.25 million loan to assist with cash flow, staff payroll and costs associated with the bankruptcy filing.

The league said it hopes to set aside $400,000 toward new athlete contracts and has alluded to staging another season of events despite ongoing bankruptcy proceedings.

At its launch announcement in 2024, Grand Slam Track drew a wave of headlines with McLaughlin-Levrone as its first signing, with promises of higher athlete prize payouts than any other promotion in the sport. By early last year meets in Kingston, Jamaica, the Miami area, Philadelphia and Los Angeles were confirmed.

The Kingston showcase, the league’s inaugural event, was panned for its low crowd turnout despite some of the top talents in track competing. In the bankruptcy filing, the Kingston meet apparently caused a potential investor to back out of funding the venture. The Miami and Philadelphia events in May fared far better but the cancelation of the Los Angeles meet in June led to speculation about Grand Slam Track’s status — and future.

Johnson would later address the league’s financial situation in several open letters and videos as rumors of athletes not being paid persisted. And prior to its bankruptcy filing Grand Slam Track asked its creditors to accept half of owed payments as a measure to help save the league, with notable vendors like World Athletics rejecting the proposal.